Who owns the fruit of your labor? In any society based on voluntary exchange, you do. The alternative, i.e. that you do not, carries implications that end up in some form of slavery, so anyone who has even the slightest affinity for liberty should reject that alternative out of hand.

Each of us routinely sells the fruit of our labor to others, but that doesn't change the fact of our initial ownership, and when we sell the fruit of our labor, we receive the fruit of someone else's labor. Almost always, with the exception being barter, that receipt is in the form of money. Money is merely a means of exchange, a fact that we may sometimes forget.

A part of the fruit of our labor is taken by the government to pay for the things the government does. Some of those things are goods and services provided to us, such as national defense, the court system, policing, roads, and the like. As I've written in the past, these fall into a "fee for service" category, meaning that we can debate the mechanism of paying for them, but they do need to be paid for. Other things the government spends our tax dollars on, not so much. But, no matter that distinction, it remains that the government is spending our money, the fruit of our labor.

This is why I seethe every time I hear a politician or read a reporter talking about the "cost" of tax rate cuts, as this Wall Street Journal article headlines.

Cutting tax rates does not "cost" money. For it to cost money, the money would have to belong to the government in the first place. Allowing taxpayers to keep more of what they earn is not a "cost."

Nor, if we move past the (important) semantic point, is there any principle exercised by government that requires a decrease in tax rates to be offset by a cut in spending? Not only is there no requirement that the federal budget be balanced, tax rate cuts are not the same thing as tax revenue decreases. While there is disagreement over whether and by how much the Trump tax reforms raised or lowered revenue (shocked you are, I'm sure, that something with the Trump name attached would generate discord), both the Laffer Curve and Hauser's Law reinforce the difference between rates and revenues.

The Laffer Curve is a "so obvious it's amazing it took so long to figure out" thought experiment. Start with the premise that an income tax rate of 100% would discourage everyone from working, and therefore produce no tax revenue. Barring coercion, why work if you don't get anything for it? So, 100% of zero is zero. Since a tax rate of zero will also produce zero revenue, and since any tax rate in between will generate some revenue, the relationship between tax rates and tax revenues looks like this.

The utilitarian who seeks to maximize government revenue should seek to find the tax rate(s) that match the peak of the curve. Utilitarianism aside, though, the takeaway is that a change in rates does not necessarily translate into a commensurate rate in revenues. In fact, if rates are too high, cutting them increases revenues, in this simple but irrefutable model's sense.

The Laffer Curve is predicated on human behavior. The bigger bite the tax man takes, the less incentive there is to work past a subsistence or baseline-lifestyle level. If you want to increase your living standards but the government is going to take 90% of every next dollar you earn, you might be more inclined not to.

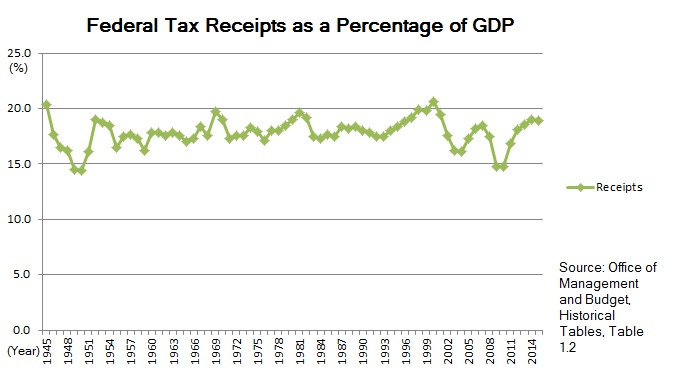

This, in the macro scale, is what Hauser's Law is about. Hauser's Law is the observation that federal tax revenues are a steady, long-term average of 19.5% of GDP, despite wide changes in tax rates and tax code provisions.

Hauser's Law is also an indicator of human behavior, and it refutes the "cut tax rates/lose revenue, increase tax rates/increase revenue" supposition.

Unlike the Laffer Curve, which suggests an optimal tax rate for revenue maximization, Hauser's Law tells us that revenue maximization is only dependent on economic growth, so setting tax rates that maximize growth should be the objective.

Unfortunately, people, politicians, and the Congressional Budget Office all think in static terms and continue to correlate rates and revenues. In the CBO's case, that's statutory, so they really can't do otherwise. But, we and our representatives should know better. Neither Laffer's Curve nor Hauser's law are inscrutable or esoteric, and we can all understand that people change their behavior when the rules change.

The government should be doing two things: setting tax policy so that GDP growth is maximized, and cutting spending (or at least holding it steady) so that the nation can trend, across years, toward a balanced budget. Practically speaking, this will also require entitlement reform, but I won't get into that here other than as a mention.

Back to the original point. This "tax cuts cost money" trope is not only wrong and offensive, it misleads and deflects us from what should be talked about and what should be done. Don't fall for it, and call it out whenever you see someone else asserting it.

I somehow lost the first sentence of this post in publishing it. Corrected, and apologies to the email recipients.

Amazing and ironic how a tax cut has to be "paid for" and yet piling another trillion onto the debt by handing out cash to favored constituencies is never given similar consideration.