The U.S. Supreme Court recently made its ruling favoring Lorie Smith, a web designer who declined to create a site for same-sex couples. Since then, the politicians, pundits, and other dissenters have gone bonkers. This is blatant hate, homophobia, and transphobia! So they say. The Supreme’s majority rationale was based mainly on the First Amendment, reasoning that her Freedom of Speech and Religion rights were violated.

Speech? Homophobia? Religion? LGBTQ rights?

Baloney. All of it. This and other related issues are not about all that peripheral stuff. What it IS really about is simply the right to say “No.”

We all have (or should have) the right to say “No” anytime, anywhere, for any reason. If someone asks you to do something you don’t want to do, you should be able to answer “No,” and the discussion is over. Your reasons are irrelevant, and nobody’s business but your own. Don’t complicate the issue with all this talk about religion and LGBTQ rights.

Whenever your right to say No is violated, that is coercion - using force, or the threat thereof, to get one’s way. Thus if you ask someone to, for example, bake you a cake or design you a website and they say No, but you refuse to take No for an answer, then you must break out the coercion. Not exactly the formula for life, liberty, and a peaceful, orderly society.

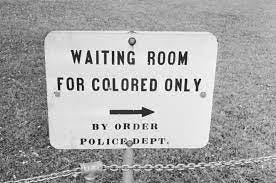

Are there people or businesses or merchants out there who say No for the wrong reasons? For example, refusing service based on skin color or sexual preference or something thereabouts? The best way to answer this question is to depend on the free market. A merchant who rejects a potential customer makes no money. Merchants who never turn a customer away make more! Money is a much more effective weapon against bias and discrimination than the harshest anti-discrimination regulations. And it doesn’t require lawyers and courts and government enforcers to get involved.

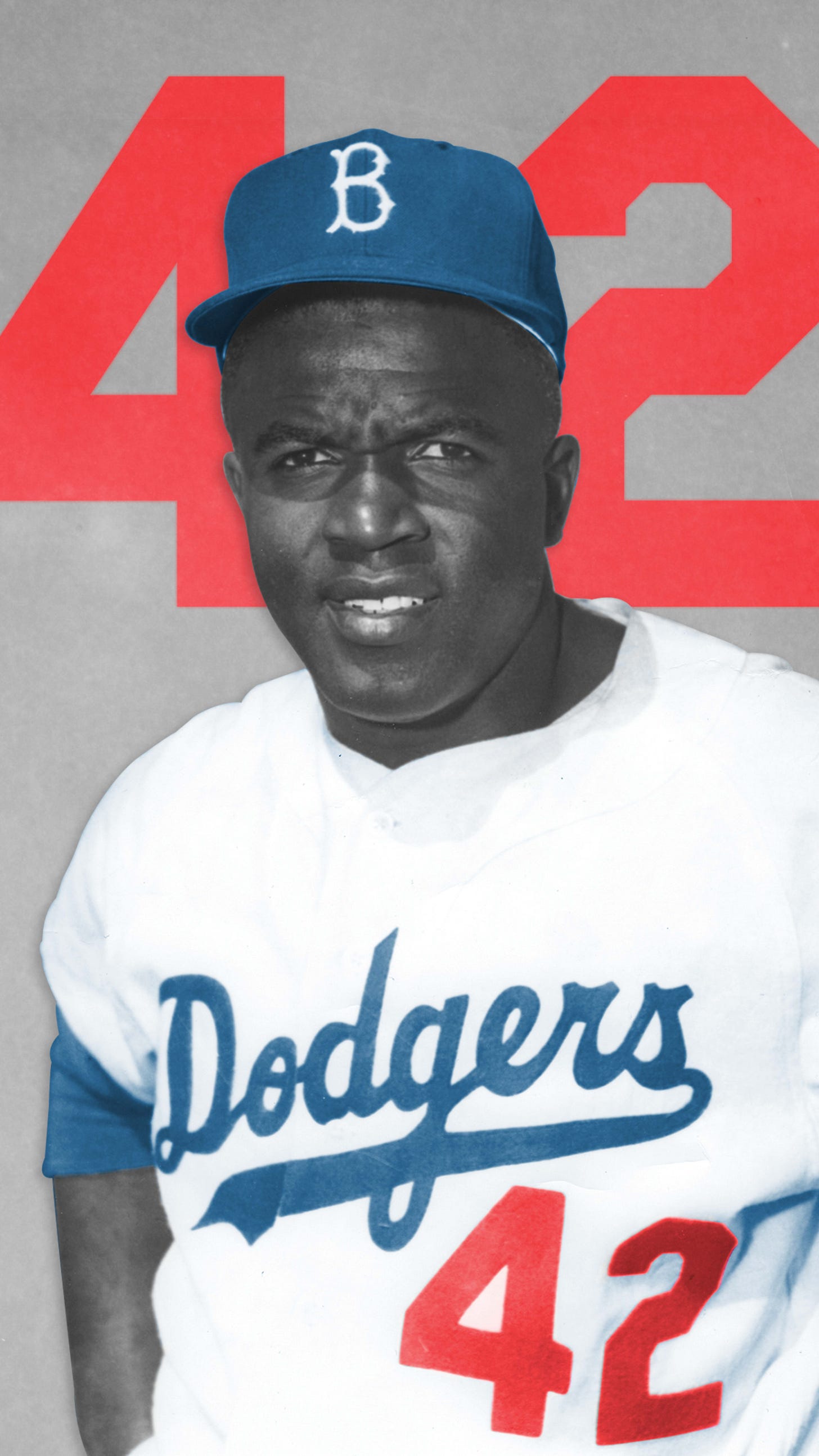

A great example of this idea in action was in the movie "42," a biography of baseball legend Jackie Robinson. In the story, the bus carrying the negro baseball players stopped for gasoline. But the racist white gas station owner refused to let the men use the restroom. So Robinson told him: never mind, our bus will go somewhere else to fill up. The gas station owner realized that giving up $90 in sales wasn't worth it, so he relented. Money motivates cooperation.

American society has come a long way since then. There was a time when unjustified discrimination was prevalent. Does it still exist? Maybe, in small pockets, but shrinking all the time. Give the credit to the power of the market - not to bureaucratic regulatory micro-management.

The principle extends also to employment. If a businessman is hiring employees, then the guy who signs the paycheck has the right to say No to any job-seeking applicant. Reasons for rejecting a candidate are nobody else’s business. But a smart businessman understands that hiring the best people, regardless of race or other immaterial garbage, is the best way to make big profits.

The "equal opportunity" crowd will, of course, scream that this will allow employers to reject candidates for the wrong reasons. But to enforce anti-discrimination laws, you’ll need governmental red tape involved in every step of the hiring process. Do you really want to conduct job interviews with a lawyer and a bureaucrat looking over your shoulder, ready to overrule your decision? Enforced with threats of fines or imprisonment?

Most people grasp the concept that we, as citizens in a civilized society, cannot and must not use coercion against our fellow man. But, there’s this odd notion out there that says that if the coercer is a government employee, then it’s Ok. Go figure. The whole idea behind freedom and liberty is that government is not “better” than us and so should abide by the same rules as everyone else. Wouldn’t it be nice if we could tell the government “No” - say, when the tax man calls - and that be the end of it?

Applying this principle, should Harvard, as a private organization, be allowed to continue race-based affirmative action?

The right to say no has become grotesquely complicated.