About a decade ago, I retired from my (second) career as a restauranteur and embarked on my (third and current) career as a commercial real estate investor. Among the many pieces of sage advice I received from the well-seasoned advisors I had back then was to be wary of doctors as tenants. The narrative was that they weren't the best operators, or businesspeople, if you prefer. The conclusion drawn, and one I've heard from other angles, is that doctors tend to overestimate their expertise in everything else. As I recently blogged, this makes them more susceptible to scams, for the simple reason that they think they're too smart to be scammed.

In a similar vein, my years of cruciverbalism have occasionally led me to encounter "I'm smart and well-read, I should be good at crosswords" presumption in others. I am, by some measures at least, smart and well-read, but I never made that sort of presumption before I started doing the puzzles in earnest, and I quickly realized that solving them isn’t simply knowing stuff or trivia, but a particular skill that improves with repetition.

On the flip side, there is an interesting observation I heard Thomas Sowell make - that,

[B]efore so many people went to colleges and universities, common sense was much more widespread.

Sowell went on to talk about how some of our most noted intellectuals have, today, incentives to venture beyond their competence. He specified Noam Chomsky (linguistics) and Paul Ehrlich (entomology) as two people we'd never have heard of if they stuck to their fields. The linked vid starts with another example - Neil deGrasse Tyson - who has cast a net far wider than his astrophysics bona fides in opining on such matters as transgender athletes. Tyson picked a side on the political spectrum, and as a result (in my opinion at least) has fallen prey to audience capture.

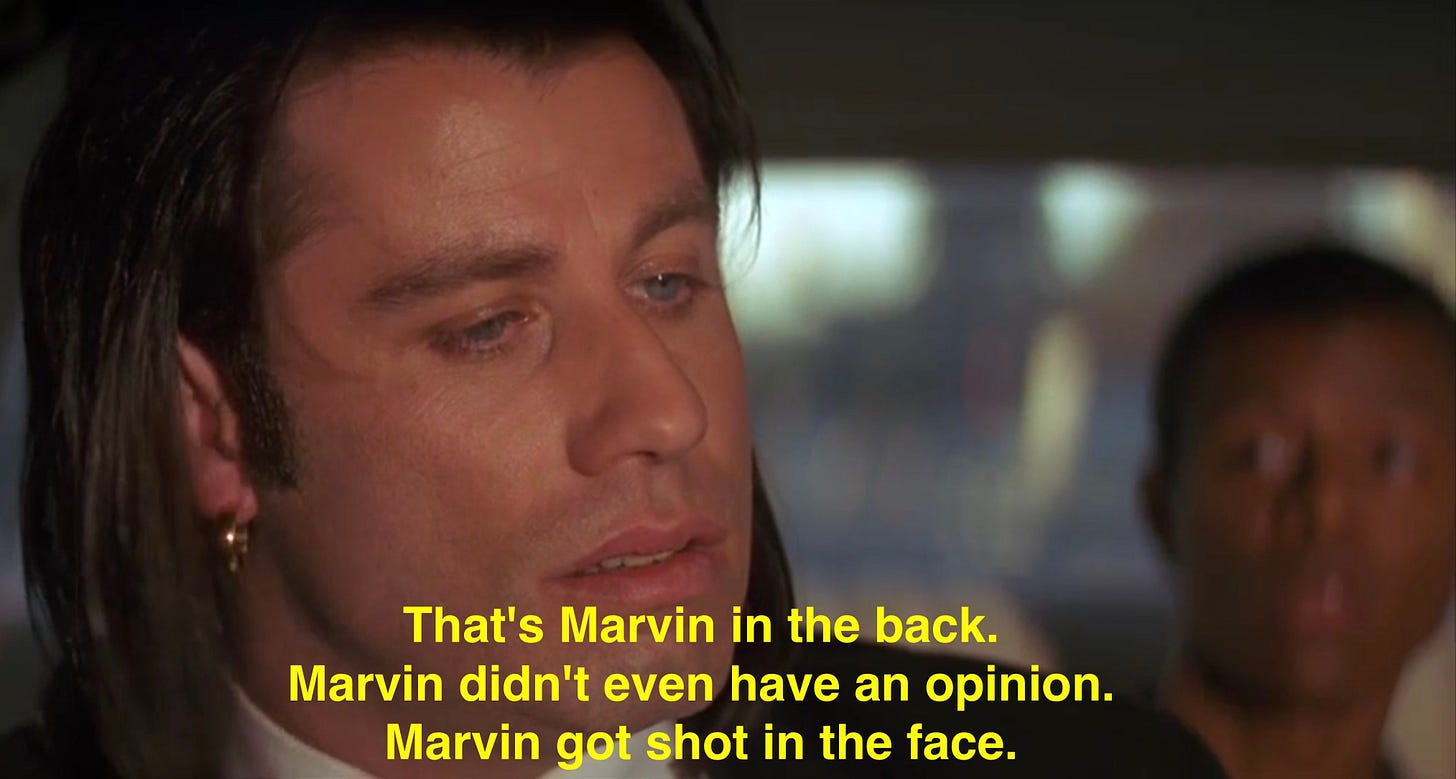

I do not mean to suggest here that someone who has degreed in a particular topic cannot develop knowledge and competence in others. Quite the opposite - I reject the exclusivity of “degreed” or pedigreed or sanctioned or licensed expertise. I've learned a lot about a lot across my decades, and this blogging habit of mine leads me to learn more about more all the time. But through all this I've also learned how little I know about countless other things, and I either try not to offer opinions when I'm out of my depth, or couch my opinions with caveats as to my limited knowledge.

The problem we encounter is not that many top-of-their-field intellectuals offer opinions on ex-specialty matters. It's the vehemence with which they press those opinions and the willingness they have to impose them on the rest of us.

The Sowell clip concludes with a lament that present-day incentives (including but not limited to social media, the echo-chamber and log-rolling nature of academia, the twenty-four hour news cycle and its endless thirst for talking head experts, and money) lead society's intellectuals (his word) to assume that high achievement in a particular field makes them qualified to be 'general philosopher kings.'

All around us, we are told to trust the experts. In a society increasingly reliant on experts to grow and function, it's good advice. If I contract a disease, I'm far more apt to trust doctors than homeopathic "medicine" hawkers, astrologers, or other quacks. But, I'm not going to throw my own common sense out the window, and I will always remember that doctors are no different from other humans. Some are better than others, some are more honest than others, some are more susceptible to conflicting incentives than others. Likewise, I will listen to experts in other topics, but if something doesn't sound right, I'll get second opinions or dig into the data. If I offer you advice and you don't take it, I won't get cranked up unless your actions or negligence do me harm. Most of us will get multiple estimates for large home improvement projects rather than accept the first contractor's numbers, and no contractor worth doing business with will get outraged if you don't hire him.

Our philosopher-kings do get outraged, however. Their proxies - the people who appeal-to-authority by quoting them - also get outraged.

With that outrage comes the desire to coerce. That's the "king" part of philosopher-king.

An Internet acquaintance recently asked whether persuasion is coercion. My reply is that conflating the two dilutes coercion down to meaninglessness. There is a fundamental difference between trying to persuade someone to conclude as you have, to see as you do, or to act as you would, and using force on them. Yes, many of the intellectuals that fall into the "I'm expert on everything" trap come at us in a persuasive fashion, but I see too many of them siding with the coercers in government, academia, and business not to conclude that they are ready to push when not heeded.

This isn't a new problem. The notion of the technocrat has always appealed. We are evolutionarily wired to distrust uncertainty and to defer to expert authority. Socialism and its ilk rely on the premise that central planning is superior to the invisible hand. Progressives of a century ago sought to control everything, including childbirth itself, so as to make society "better." We know how well that has worked out.

What is new is the degree to which the intellectual class has cocooned itself. As Bari Weiss notes in this video, they are now a "micro bubble of an elite group of Americans speaking to each other." Absent connection to the rest of the world, they grow more convinced of both general-expertise and infallibility, with the noblesse oblige coercion as a natural result.

Yes, I've thumped this particular drum many times, but until enough people break away from blindly heeding their favorite experts' pronouncements on everything and using those experts as an excuse to dismiss disagreement and look down on disagreers, we're never going to get back to a marketplace of ideas or a government that serves rather than rules.

I democratically anoint you, Peter, my libertarian philosopher king. For now. That can of course be revoked on any given day - and that's as it should be. Each of us have to get up each day and prove our words' worth to others. I've noticed among the government authoritarian "kings" they don't provide receipts - links to studies and data - so we can authenticate what they're saying. Or they cherry-pick or rig the data they provide in justification of their pronouncements. They got away with this for only so long as the "mainstream" (now misinformation disinformation propaganda) media complex had a monopoly. But those days are over. We anoint those who provide receipts and show their math.

“If I offer you advice and you don't take it, I won't get cranked up unless your actions or negligence do me harm.” This sentiment empowered so many to be outraged by nonconformists through the pandemic.